Velež Mostar’s former football stadium Bijeli Brijeg exemplifies the wounds still present from the Bosnian war. But the club’s plans for a new stadium is also a hopeful sign of reconciliation in a divided city.

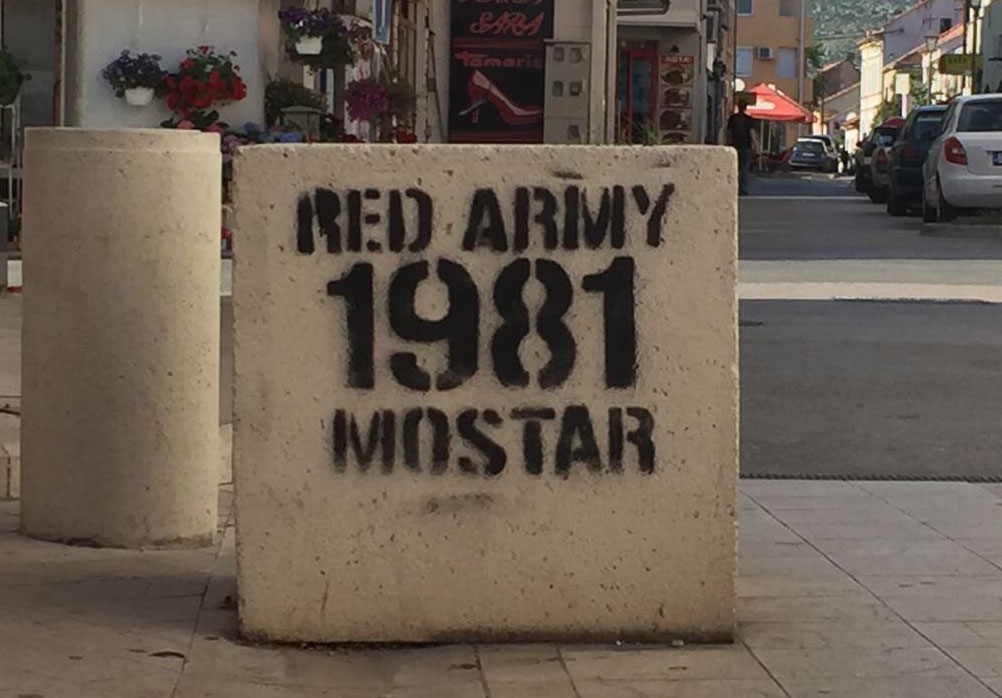

The graffiti on Mostar’s Maršala Tita street look like someone marked a territory. Close to the train station a spray-painted young man wears a baseball hat and is disguised with a scarf on an abandoned building. „Urban Guerilla“ is sprayed next to him. A few blocks down the street it says „Red Army Mostar 1981“. Towards the end of the street a modified version of the Che Guevara icon with sunglasses and a beret is sprayed on a rundown building marked with bullet holes. „Red Army“ is the Ultras fan club of Mostar’s football club FK Velež. The message behind these graffiti is: This is our club, our neighborhood and our city.

Left wing history on a war-torn building: Velež’s supporters club Red Army was founded in 1981

Left wing history on a war-torn building: Velež’s supporters club Red Army was founded in 1981

The recipients of the message are to be found a few hundred meters west from Maršala Tita street on the other side of the Neretva river: the fans of HŠK Zrinjski Mostar – the second football club in the city. Mostar’s landmark Stari Most (Old Bridge) connects the two parts east and west of the river. But these days it hardly bridges the city’s divide in terms of ethnicity, politics and sports caused by the Bosnian war.

When Velež and Zrinjski play against each other the clubs’ hardcore fan groups often end up in fights. And just like on the Eastern part of the city, the Ultras from Zrinjski have also marked their territory with graffiti. Their message: This is our club, our neighborhood, our city and – especially – our stadium.

Zrinjski fans attacking on the pitch after a goal from VeležBut this was not always the case. Before the war broke out in 1992, Zrinjski’s stadium Bijeli Brijeg was the home ground of FK Velež. And the city’s football fans were not divided between two clubs but gathered in the stadium to support Velež Mostar together. Like they did on November 4, 1987.

Writer Marko Tomaš was one of 35,000 spectators who gathered on this Wednesday in November at Bijeli Brijeg to support Velež against Borussia Dortmund in the second round of the UEFA Cup. Bijeli Brijeg was packed. Officially the stadium held 25,000 people. But almost one third of Mostar’s population wanted to see Velež advance to the next round. „I was a small kid, 9 years old, and infected by the atmosphere. It was the first big sensation of my life,“ says Tomaš. Velež dominated Dortmund for most of the game and won 2:1. But this was not enough to advance to the next round as Dortmund had won the first game 2:0 in Germany two weeks earlier.

Velež’s golden generation of the 1980s beats Borussia Dortmund in front of 35,000 fans

The bitter win was the last big sensation Tomaš and football fans in Mostar experienced first hand. 30 years later, Dortmund is one of the most successful football clubs in Europe. Whereas Velež – down and out – struggle to stay in professional football in Bosnia’s second league. „Today it is impossible to even think that Velež could reach such a level again,“ Tomaš is convinced.

The decline of Velež is symptomatic for the wounds still present in Mostar. 22 years after the Dayton Agreement ended the war in Bosnia and Herzegowina, the city has still not recovered from the pain inflicted – mentally and physically. And the story of football in Mostar tells us why.

For a city with hardly more than 100,000 inhabitants, Mostar has a remarkable football history. Founded in 1922, many football fans in Yugoslavia called Velež their „second favorite team“ and it was one of only two clubs from Bosnia and Herzegovina to have ever won the Yugoslav Cup (1981 and 1986. The other one is Borac Banja Luka in 1988). Wearing red jerseys, the club was connected with leftist politics and multi-ethnic ideals in socialist Yugoslavia. Mostar was regarded as one of the most ethnically-tolerant environments in the country before the war. The city also had a comparatively high percentage (10%) of mixed marriages between Bosniaks, Croats and Serbs.

Zrinjski Ultras graffiti close to the stadium

Zrinjski Ultras graffiti close to the stadium

But in the shadows of Velež’s success the story of another club shaped the history books of football in Mostar. HŠK Zrinjski Mostar (Croatian Sports Club Zrinjski Mostar) was founded in 1905 by the Croatian population of Mostar and was the rival of Velež at the beginning of the 20th century. But due to the club’s connection to Croatian nationalism, Zrinjski were banned after World War Two. Almost 50 years later the rivalry erupted again when the war in Bosnia broke out. In the centre of the conflict: Bijeli Brijeg – the stadium that once brought the city together to cheer for a win over Borussia Dortmund.

On May 9, 1993, the Croatian Defence Council (HVO), the main military force of the Croats in the country, forced Bosnian Muslims in West Mostar out of their homes and gathered them at Bijeli Brijeg. Most of the Bosniaks living in West Mostar were expelled from the city or put in detention camps. Mostar by then was already a divided city: the Western part was mainly inhabited by Bosnian Croats and the Eastern part inhabited by Bosnian Muslims. Most of the Serbian population had been expelled or left the city by then.

Mostar’s old bridge connected the city for more than 400 years before it was destroyed during the war on November 9, 1993. Afters years of reconstruction it was reopened in 2004.

At this time the stadium no longer belonged to Velež. With the Croat forces taking control of the Western part, Velež lost their beloved home ground and the old rival Zrinjski moved into the stadium. Zrinjski, banned for almost 50 years, was re-founded shortly after the war broke out in 1992 and seized the opportunity to call Bijeli Brijeg their new home. Velež had to look for a new stadium after the war and moved to Vrapčići, a village north of Mostar, transforming a dusty football ground into an improvised 5,000 capacity stadium.

Writer and Velež fan Marko Tomaš, who did not live in Mostar during the war, tried to reconnect with the club he cheered for as a boy, but something was lost. „It was not just about the club and Velež not playing in the old stadium. It was the city in general. The spirit had changed and it felt like growing up in a new city again.“ In the divided city, the rivalry between the two clubs turned into shadowboxing for blaming the other side for atrocities committed during the war „Mostly young men who identify themselves through the group and their national background are responsible for the fights at the games,“ Tomaš claims.

Maršala Tita street and its graffiti: Velež, Red Army and urban guerilla

Maršala Tita street and its graffiti: Velež, Red Army and urban guerilla

Many of these young supporters were born after the war. Their anger can not simply be explained by a past they have hardly experienced themselves. They are frustrated with a city and country stuck in corruption, nepotism and economic stagnation. Embittered with a status quo that does offer few opportunities to move forward. Bosnia ranks among the countries with the highest youth unemployment rate in the world (around 60%). In addition, Mostar has not held communal elections since 2008 because of arguments concerning the administrative structure of the city. There is hardly a public institution that does not exist twice: two energy suppliers, two telecommuniaion providers, two universities, separated schools and two different football clubs. The stadium is one of the few places, like everywhere else in the world, to let out the anger. Except for Mostar, the anger is embedded in recent war wounds and a political landscape that fosters division instead of cooperation.

On the walls of Bijeli Brijeg: Zrinjski’s connection to the Croatian community shows in the club’s logo with the checkerboard

On the walls of Bijeli Brijeg: Zrinjski’s connection to the Croatian community shows in the club’s logo with the checkerboard

Whereas most of Zrinjski’s supporters belong to the Croatian community, Velež still tries to live up to their multi-ethnical background. But with less and less success. With most of the Serbian population having left the city and the Croat population cheering on the other side, Velež draws the great majority of fans from the Bosnian Muslim community. The consequence: Velež’s once diverse Ultras fan group Red Army has also moved towards Bosniak nationalism. „Velež fans are still talking about themselves as being left wing and it is cool to have a red star on your chest. But there is nothing left wing about nationalism,“ Tomaš says with disappointment.

But identity based on ethnic belonging is not just an issue the two football clubs of Mostar struggle with. With nationalism on the rise throughout Europe, the rivalry between the ultras of Velež and Zrinjski finds resonance on a larger scale. Tomaš: „The values on which Europe is based are falling apart. As a small country this is not helpful for Bosnia as we need to look up to a larger political scale. But on the European level it is also chaotic.“

Velež’s once diverse Ultras fan group Red Army has moved towards Bosniak nationalism

Velež’s once diverse Ultras fan group Red Army has moved towards Bosniak nationalism

How heated the situation still is, was recently exposed by a concert played by the Croatian singer Marko Perković aka Thompson. Perković, a nationalist and war veteran, was regularly banned in the past from performing in Europe and the US due to glorification of Croatian fascism in World War Two. On May 9 this year he held a charity concert at Bijeli Brijeg in support of Croat officials currently on trial at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in The Hague. They have been convicted in the first instance for expelling the Muslims of West Mostar and gathering them at the stadium during the war on the exact date 24 years ago. A provocation that rubs new salt into old wounds.

Even though the hardcore fans of both teams are unwilling to reconcile, the clubs’ officials and players are trying to move forward. “The relationship between the clubs is alright. Many of the players have known each other all their life and are even hanging out together,“ says Tomaš. He adds: „But when the political situation gets heated, the clubs get under pressure too.“

What matters first and foremost to the clubs is nevertheless success on the football pitch. Velež’s new stadium project could be a helpful step towards normality and a future based on reconciliation. In 2016 the club presented plans for the expansion of the Vrapčići stadium into a modern 10,000 capacity arena. Construction work has started this summer and the new stadium has gained shape by the beginning of the season in August.

Towards normaility and reconciliation? Velež’s plans for their new stadium

Step by step Velež are trying to move forward and building a proper new home for the club that once travelled all over Europe. „It would be nice if Mostar would have a normal football rivalry in the future. I don’t care about the division of the city,“ says Tomaš.

And perhaps one day the 39-year-old will be able to connect with the first big sensation of his life and witness Velež play a European game again.

On the right or wrong side of town? Stadium Bijeli Brijeg in Mostar

Velež Mostar

Founded in 1922, currently playing in the second league in Bosnia and Herzegowina. During the existence of Yugoslavia Velež was considered to be “everybody’s second favorite team” admired for its creativity and energy. Won the cup in Yugoslavia twice in 1981 and 1986 and made it to the UEFA cup quarterfinals in 1975. Hasan Salihamidžić, Bayern Munich’s current sporting director, played for Velež before he left for Germany. Other well known former players include Sergej Barbarez, Semir Tuce or Nenad Bijedić.

Zrinjski Mostar

Founded in 1905, but banned in Yugoslavia due to their connection to Croatian nationalism. Founded again in 1992. Most dominant team at the moment in Bosnian football having won the league title in 2014, 2016 and 2017. Despite the success in Bosnia, Zrinjski did not qualify for the group stage of any European competition. Zrinjski’s most famous players is Luka Modrić (Real Madrid) who played at the beginning of his career 2003-2004 for the club.

Marko Tomaš

Born in 1978 in Mostar, wrote several books of poetry and a biography of Ivica Osim – Ex-Yugoslavia’s and Bosnia’s most successfull football coach. After years inSarajevo, Split and Zagreb he has been living again in Mostar for the last coiple of years.

The city: Mostar

The largest city in Herzegowina, the southern part of Bosnia and Herzegowina, has about 115,000 inhabitants. During the war about 2,000 people died – civilians and combatants. Ten thousands fled, but the majority came back after the end of the war in the late nineties. Before the war, the Mostar municipality had a population of 43,037 Croats, 43,856 Bosniaks, 23,846 Serbs and 12,768 Yugoslavs. Most of the Serbian population has left the city (around 5,000 remain). Mostar has not held communal elections since 2008 because of arguments concerning the administrative structure of the city practically dividing the city into two parts. Besides the Old Bridge and its surroundings, other places to check out are the partisan memorial, OKC Abrašević cultural centre and the Karađoz Bey Mosque. The landscape surrounding Mostar also offers great hiking and rafting opportunities.

The country: Bosnia and Herzegovina

The country declared independence from Yugoslavia on March 3, 1992. The following war killed more than 100,000 people and was ended with the Dayton agreement on December 14, 1995. Since then economic and political progress has been slow. Since the end of the war approximately 150,000 young Bosnians have left the country, and around 10,000 young people still leave the country each year.

In 2016 the unemployment rate was about 25 percent. Youth unemployment was even higher than 65 percent. Bosnia has a population of approximately 3,5 million people with an average salary of around 400 Euro. The political system of the country, which has been based on ethnic identity since the war, is considered to be one of the world’s most complicated systems of government.

When dealing with such a contested subject and history, it is perhaps important to rely on and cite more than one narrative, one source of information.

thanks for your comment! fair enough! what would you add to the story? Best, Stephan